sika hind with calf

Introduction

The aim of this guide is to highlight features of the biology and behaviour of Sika (Cervus nippon) to aid in the management of the species, it is not a complete description of sika ecology (see Further information below). Deer behaviour is not fixed, they will adapt their behaviour to local circumstances, sometimes behaving quite differently from one area to another or over time. This guide links to Deer Biology, Deer Behaviour and Deer Signs guides which should be considered as important associated reading.

Social structure

Herding animals but very changeable in the way they associate, it is just as common to see small groups of animals (often a hind and her yearling and calf, or small stag groups, as it is to see larger herds, the size of the groups depends on habitat type/quality, deer density, degree of disturbance, time of year, and weather. Very large herds are possibly the result of high deer densities, continual disturbance, animals gathering on a food source or prolonged hard weather.

Sexes are usually segregated for most of the year, stags will move into hind areas during the rut.

Stag groups have a hierarchy based loosely on age, size and aggression, hinds tend to be matriarchal, led by a dominant female who can sometimes be identified when the group is disturbed. Calves are dependent on their dams until 3-4 months but may suckle for longer. Female calves tend to remain with their dam and her group, hind/calf/yearling groups are common. Young stags disperse after a year or so to join bachelor groups.

Patterns of activity

Use of Habitat

Prefer woodland or thicket and graze on nearby open areas such as farmland or heath/moorland. Often adopt quiet areas as “sanctuaries” where they can remain undisturbed. Mature hinds (and therefore their immediate followers) may be very limited in their range, sometimes less than 1km2 over several years, and be strongly hefted to those areas. Stags are far more mobile.

As a herd sika may move several miles from where they lay up during the day, to where they graze. If undisturbed they may be seen on their preferred grazing areas (usually grassland) during the day but sometimes grazing almost exclusively at night. Stags will often be seen sitting out in arable crops pre-harvest.

Routines may change due to disturbance, which can make sika unpredictable and difficult to locate.

Like most deer sika movement is affected by season and weather, some knowledge of how they respond will make them easier to predict, see Deer Behaviour guide.

Feeding

Primarily grazers but can have a very diverse diet. Often graze on open areas, especially grassland, but will spend long periods browsing in woodlands. In hard frosts frozen grassland may be avoided in favour of heather or gorse or woody plants. Will include plants such as birch and Molinia (Purple Moor grass) in their diet which other deer might avoid. Sika are good at maintaining body condition through the winter.

Maximum browse height is approx 1.6m

Breeding

Females are polyestrous (will come into season repeatedly if they do not conceive at first). This may result in occasional births as late as September rather than June/July. Adult hind pregnancy rate is often 90% or more. Hinds produce a single calf each year, over a breeding life of 10 years or more. Late middle aged hinds are generally larger and may produce heavier, earlier calves. A variable percentage of yearling hinds may be pregnant, even hind calves may conceive. In both cases the calf may be born very late because it’s mother may have reached the minimum conception weight after the main rut.

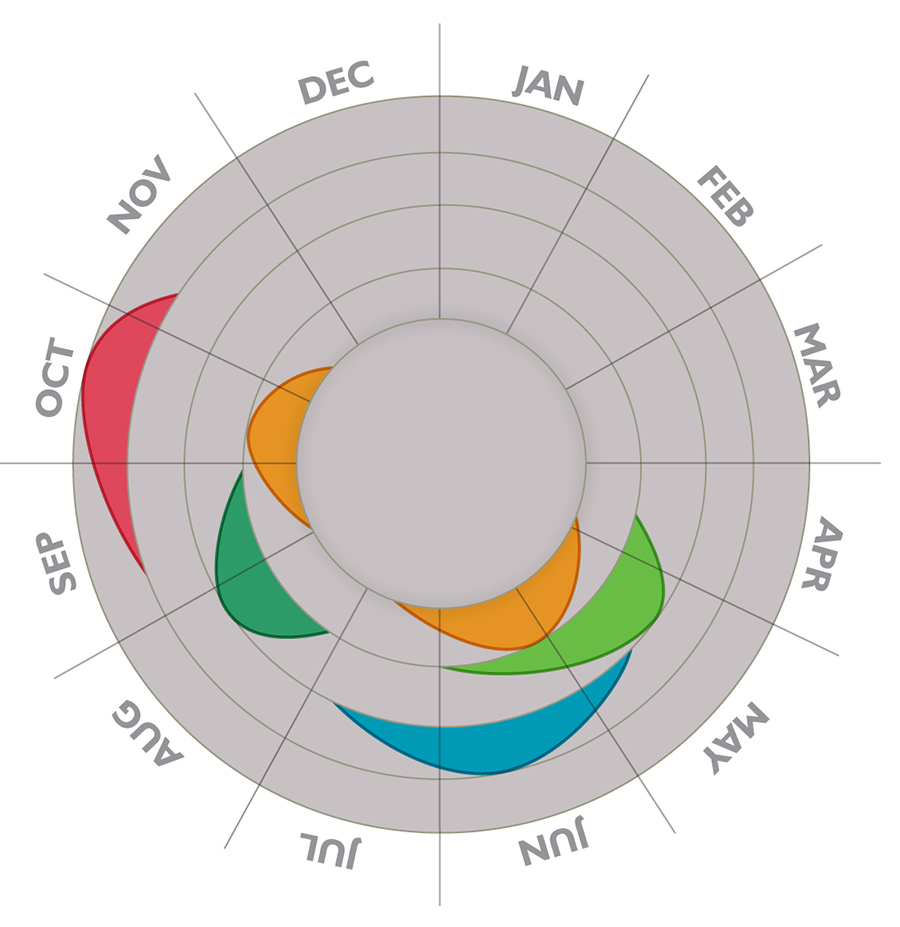

The peak of the rut is in Sept/Nov, although rutting activity may be seen in August and as late as December. The behaviour of stags at this time can be highly unpredictable. Stags may create rutting stands around wallows in traditional areas which the hinds visit, but will also mate opportunistically, seeking hinds out.

Embryo development begins immediately, by December it is easy to confirm pregnancy in culled hinds although the embryo may not be apparent until January for late mated hinds. Survival rates of calves can be very good (usually 50-90%), lowest where deer densities are high or for late calves. Survival rates improve if high density populations are reduced below habitat carrying capacity (see Cull Planning guide). Most hinds cease lactation by December but some may continue into February.

Distinguishing sex and age

Sex

Calves difficult to tell apart until males begin to develop pedicles/antlers. Adult males may have a mane in autumn and through the winter, are larger and often darker in colour than females. Where they occur together (in parks) it is possible to confuse the females of sika and fallow.

Sika antlers are often very light in colour and are usually obvious except sometimes in yearling stags. Because all of the points are in line front to back it may be harder to see antlers when animals are head on rather than from the side.

Age

Straightforward to age into the four broad age classes, calf, yearling, adult, old. Older sika tend to be stockier and broader across the back. Older hinds have longer faces, older stags have more “boxy” faces.

Juvenile third pre-molar is lost at around 18-20 months and full adult dentition is achieved by 24-26 months although the last cusp of the third molar may not come into wear until 36 months. Most wild sika are younger than 12 years old.

Size and form of antlers is some indicator of age in sika, yearlings usually have simple spikes, brow and trey tines usually develop in the second head with top points appearing later. The presence of a bey tine possibly indicates a red/sika hybrid. The antlers of very old stags may decline in size. In general the pedicles will be shorter on older stags.

Condition

young stag- winter coat

Coat change normally April/May and Sept/Nov (youngest first). Antlers cast from April (oldest first)and become clean from August. Very late antler growth or coat change may be an indicator of poor health. Sika are most often in very good condition as judged by fat cover. Late born or poor calves and poor adults may appear fluffy and ginger haired.

Culling

Mature stag. Differs from red stag in that there is no bey tine on antlers. Hock gland is white/cream. Rump patch does not run up onto back

Strongly hefted hinds can be relatively easy to cull but continual pressure will cause them to become nocturnal or change their behaviour. Stags can be much more unpredictable, moving over very large areas and changing their behaviour in response to disturbance. Because they are herding animals care is needed when shooting to avoid injuring others in a group.

Sika will sometimes be found in wide open spaces, making them easier to see but more difficult to approach.

Usually culled using a combination of stalking and sitting out (in high seats and other vantage points), mainly in the early mornings and late evenings although in mid winter sika may be on the move at any time of day even in very poor weather. Moving sika to static rifles can also be productive(see Moving Deer guide).

When culling hinds, the welfare of their calves must be taken into account. Culling hinds without young avoids the issue, but these are likely to be a minority of those that have to be culled. Where possible dependent calves should be culled before or immediately after their dams, especially early in the season before the calves become more independent. If a dependent calf is unintentionally orphaned strenuous efforts should be made to cull it. If this is not possible immediately, the calf will normally be found with the herd later and should be culled then if it shows signs of deterioration. If the hind and calf were alone, the calf will often return to the shot hind within the hour. Later in the season orphaned calves are far more likely to do well but, if practical, continue to cull calves with their dams. Calves in poor condition should normally be culled as a matter of course.

When culling on a landscape scale some general principles apply:

Keeping the herd as settled as possible is key to success, sika may become unpredictable when disturbed.

Try to leave some areas where the deer feel safe, this makes them more predictable, but this should not be at the expense of creating “sanctuaries” where numbers are allowed to get out of control, thus affecting the outlying areas.

Especially early in the season concentrate on isolated family groups, preferably on the boundaries and away from resting areas, this reduces the risk of disturbing large numbers of deer at once and increases the chance of culling calves/yearlings with their dam.

It sometimes pays to try to get the more awkward animals first, leaving the easier ones till later, this applies both to the harder to get at groups and to the flightier animals within a group.

By preference tackle larger herds later in the season. Having fired the first shot(s) do not chase the herd just to get one more, leave them to settle.

It is wise not to always stalk the same areas and in the same way, or too frequently.

When disturbed a herd may leave en-masse and not return for long periods. Such behaviour often takes them across man-made boundaries and out of an individual stalkers influence. Because of this it is usually more efficient to approach sika management on a landscape scale by cooperating across boundaries (see Cross Boundary Liaison guide).

Sika hinds may become more visible as the winter progresses but the hind herd may become more and more “savvy” as the season wears on. It may require ever changing tactics on the part of the stalker to maintain the pace of the cull.

It may be tempting to shoot stags as they create their rutting stands but this can have the effect of putting too high a selective pressure on the adult stags and disrupting the normal behaviour of the hinds just as their season opens. The venison of stags in rutting condition becomes “tainted” by their scent. By preference take stags early in the season, well before the rut or when the bulk of the hinds have been culled.

Sika have a reputation for having a keen sense of smell requiring a very careful approach with regard to the wind. They are also capable of running long distances even after a perfect heart shot, a calibre/bullet producing a good exit wound and stopping power is recommended. A shoulder shot that drops the animal on the spot can be useful in or near cover.

The culling seasons for hinds (1 Nov – 28 Feb) and stags (1 Sept – 31 Dec) overlap but it is important that, when trying to achieve the female cull, stags are not accepted as a substitute to “make up numbers”. Dependant stag calves may have to be culled for humane reasons and potentially make up a substantial part of the stag cull, thus relieving culling pressure on the older stags.

It is important to cull sufficient females to prevent over population, hinds can produce 10 calves or more over a lifetime. Culls of 20% of the population may be required to keep many populations stable and the majority of these should be hinds. (See Census and Cull Planning guides)

In many herds there is a preponderance of females, with ratios of as few as 1 stag to 10 hinds, this is partly because survival rates are lower in stags. Such low stag:hind ratios will not prevent hinds from becoming pregnant. In such cases the proportion of hinds in the cull will have to be even higher.

There is often concern about apparently low numbers of mature stags in sika populations, good cooperation across boundaries should help to ensure that these stags are not culled too heavily. In general the quality of antlers will be best when deer density is not high and where restraint is exercised when culling stags.

In good habitats adult carcass weights (empty, skin on, head and feet off ) should average around 35kg for hinds and between 40kg and 70kgfor stags depending on age. These value can vary significantly depending on the area and even animals smaller than average weight may be in very good overall condition.

Damage

sika bole scoring

The most significant impact is caused by grazing and browsing. In woodland grazing/browsing may adversely affect woodland regeneration, damage commercial tree plantings, and affect the structure and composition of the understory. Sika are known to have impacts on heathland and salt marsh. Acceptable impact levels will depend on site specific circumstances and objectives.

Stags in some areas cause “bole scoring”, they can also cause extensive bark stripping. Sika will lay up in cereal crops, which can open the crops out to wind-blow. Where stags are resident and during the rut they may cause damage by thrashing tree and shrub branches, often fraying damage is not too significant.

Hybrids

Sika and red deer may hybridise. There is a wide range of normal variation within each species and the vast majority of non-pure animals go un-noticed, tending to look like one of the parent species. There may be occasional individuals that shows signs of hybridisation, some of the signs are:

| Sika-like animals | Red-like animals |

| Unusually leggy/tall | Unusually stocky |

| Presence of any form of bey tine on antlers | Absence of bey tine (also seen in pure reds) |

| Persistent spots on flank in adult summer coat | |

| Black colour on centre of tail (dark border around rump patch is normal) | |

| Light coloured hock gland |

Further Info

Prior, R. (2007) Deer Watch. 2nd Ed

British Deer Society, Deer Identification sheet

Putman, R. Sika Deer, Mammal Society/BDS series

The International Sika Society (1995). SIKA

[printfriendly]