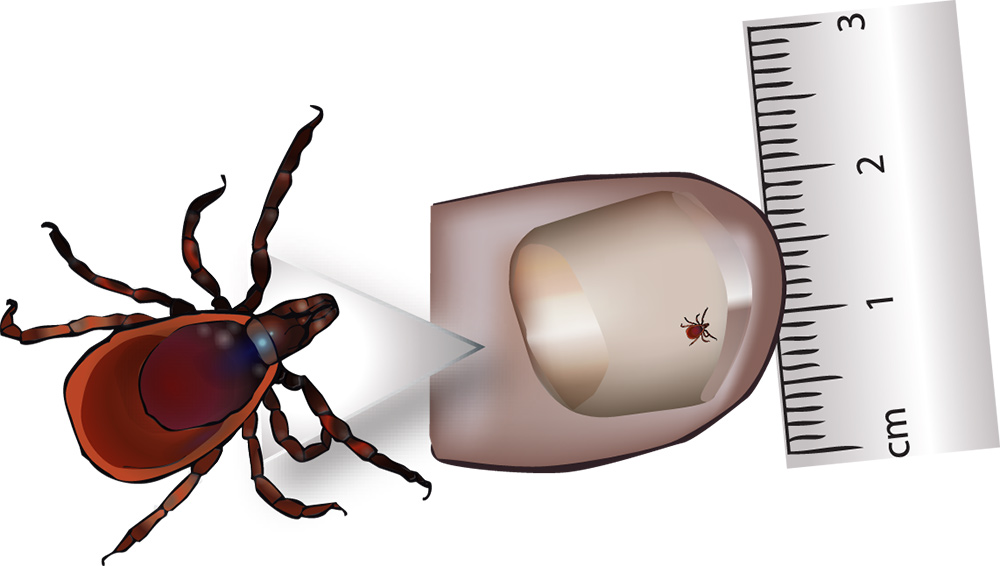

measured on a thumb, the nymph is 2mm

Introduction

Lyme disease was first described in the USA in 1974 and takes its name from Old Lyme in Connecticut, where the first outbreaks were noted. The illness had been known by a variety of names in Europe since the nineteenth century, and its relationship with tick bites was recognised in both continents. Ticks are present in many parts of Ireland and the number of reported cases of Lyme, though small, is rising each year. About 20% are acquired abroad, in other European countries or north America.

The aim of this guide is to raise awareness of Lyme disease and methods of prevention.

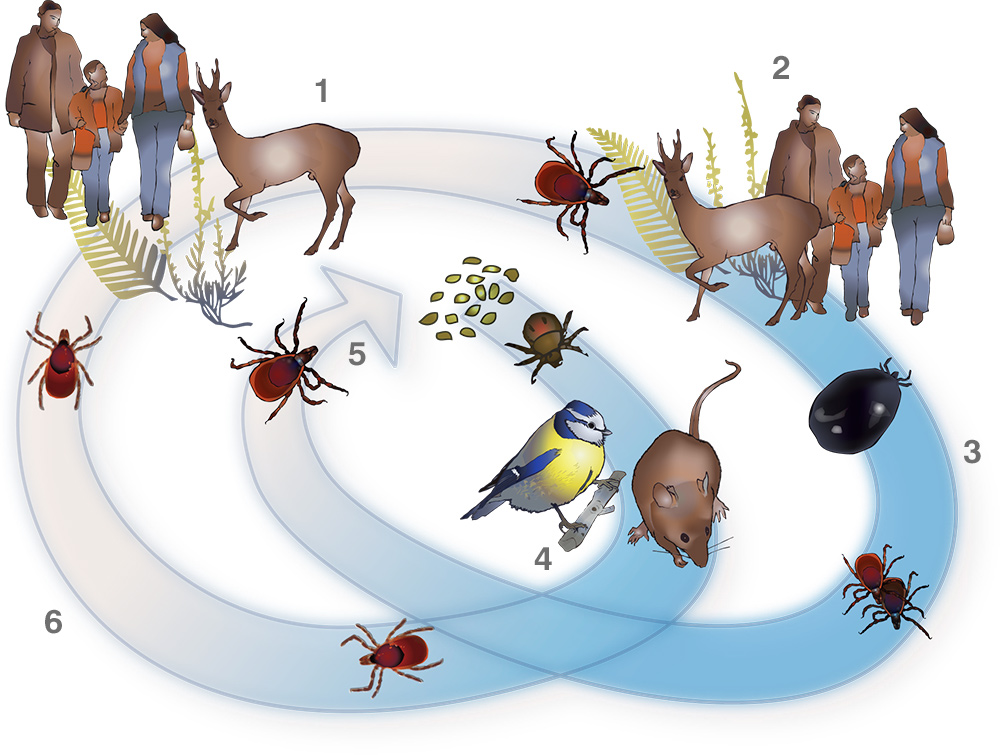

1: (Summer) after feeding on blood the nymph drops off the host and matures into an adult; 2: adults find their tertiary hosts: deer, humans, dogs etc; 3: (Autumn) after feeding an adult is enlarged out of all proportion to its original size; adults mate and eventually fall off the host; 4: ( Winter) larva use mice and birds as their first host, fall off, become nymphs and go dormant for six months; 5: at two years old the adult females lay eggs; eggs laid in spring, appear as larva during the spring/ summer; 6: (Spring) the dormant nymph wakes in spring and finds a secondary host in deer, humans and other mammals

Cause of Disease

Lyme disease is caused by the spirochaete bacterium Borrelia burgdorferi and is spread to humans (and many other mammals and birds) by the bite of the common tick, Ixodes ricinus. The tick feeds on blood at each of the larval, nymph and adult stages of its life cycle and when feeding can pick up or pass on the spirochaete. Between stages ticks leave their host, mature to the next stage then “quest” for a new host by clinging to the tips of long cover such as grass or bracken to be picked up as the host walks by.

It is thought that birds and small mammals such as mice are the main spirochaete reservoirs. These are the usual hosts for larvae and nymphs. Larger mammals such as deer and sheep are important final hosts for adult ticks, but most ticks do not carry infection at any stage of their lifecycle. The risk of infection from an infected tick attached for 24 hours or less is very low, so early removal of ticks (within hours of attachment) is effective in reducing risk of infection.

The nymph is the most important vector to humans because its small size makes it difficult to detect and it may therefore stay embedded for longer. Adult ticks are more likely to have become carriers but fortunately they are easier to see and more likely to be removed before passing on the infecting agent. Adult ticks which have fed and fallen from their host present no danger since they will not feed again. Lyme spirochaetes cannot be transmitted by eating even raw meat from infected animals and are not spread from person-to-person.

the back shows early symptoms of lyme disease, while the arm (left above) shows the disease at well developed stage.

Signs & Symptoms

Tick bites are not usually itchy or painful, and so may easily be missed. Occasionally people who have had many tick bites may become sensitised to them, and may experience mild itching. If spirochaetes have been transmitted the most common, and sometimes only symptom, is a spreading rash (erythema migrans) which may persist for weeks if untreated. Some patients may also suffer “flu like” symptoms in the period after being bitten. Either symptom following a bite or exposure to a tick environment should indicate a trip to the doctor and will form an important part of the diagnosis.

Occasionally more serious symptoms may appear after weeks or months and can affect the nervous system, joints (especially the knee) and rarely the heart and other tissues.

Facial palsy, ‘viral type’ meningitis, pain from nerve inflammation, disturbance of sensation and clumsiness are some of the nervous system complications. Lyme disease occasionally triggers a post-infection syndrome similar to fibromyalgia or chronic fatigue syndrome.

Apart from erythema migrans none of the symptoms is unique to Lyme disease, which may make diagnosis difficult.

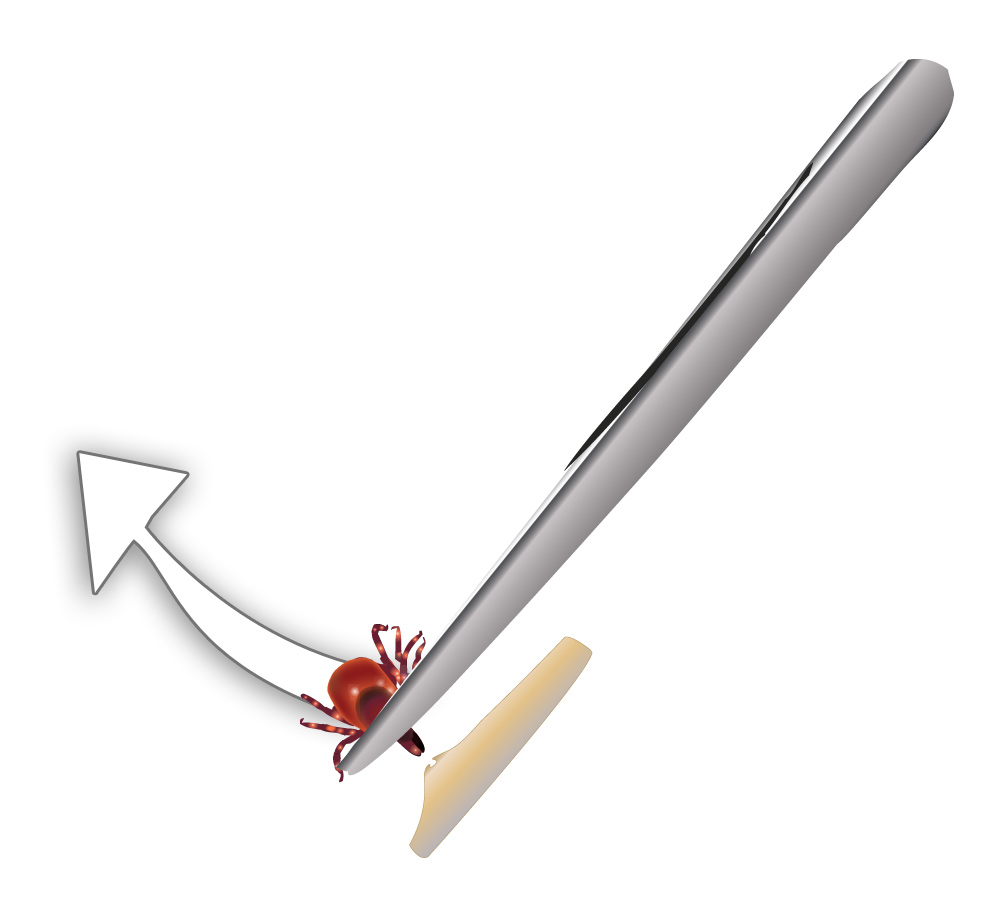

to remove hold tweezers firmly and use constant pressure to pull tick free of skin

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is easiest where there has been a known tick bite followed by a rash. Unfortunately many people are not aware that they have been bitten, which, in areas where the incidence of the disease is low, may lead doctors to mistake the diagnosis. Blood tests are typically useful only after two to six weeks following infection, as they test for antibodies (the body’s immune system response to infection), which take a little time to develop. Antibody tests are useful but not infallible, but it is very uncommon for people with late stage infection to have negative antibody tests. A positive test may only indicate past exposure to disease, not necessarily a current infection, especially in people who have had frequent tick exposure.

It is important that those at risk recognise the possibility of infection and when appropriate make doctors aware that they have experienced a tick bite or been exposed to ticks. Lyme appears to be far more common in people who have had recreational (holidays etc) rather than occupational exposure.

Treatment

Antibiotics form the mainstay of treatment for the early manifestations of Lyme disease, and are effective at preventing the later symptoms. Later stage infections also respond to antibiotics, but recovery may be slower if there has been significant tissue damage. For most patients the long term outcome is good. There is currently no vaccine for Lyme disease.

Prevention

Preventing tick bites is the most effective way of avoiding Lyme disease.

- Tick bites are most likely in spring, early summer and autumn when walking in areas of cover such as woodland, moorland, long grass or bracken. Avoid these areas where possible.

- Covering exposed skin with long trousers tucked into socks and long sleeved shirts with cuffs fastened will help to prevent direct contact. Wear boots or shoes rather than sandals.

- Insect repellents can help, especially if applied to the naked skin. Alternatively trousers can be sprayed with insect repellent or insecticide (Permethrin) impregnated clothing is available.

- Ticks can live for a long time in clothing so brushing off clothes before going indoors is a sensible precaution

Those whose workplace is outside and in tick infested areas could carry a spare change of clothing to be worn for traveling home in. - Examine for ticks every three to four hours and at the end of each day spent in a tick habitat. Pay particular attention to skin folds, e.g. groins, armpits and waistband area.

- Children especially should be checked around the scalp and face.

- Flea/tick collars or products such as Frontline will help to protect pets from ticks.

- Consult your doctor if a rash or other symptoms develop within a few weeks of a tick bite.

Removing embedded ticks:

- Remove ticks as soon as possible

- Using a tick removal hook, forceps or tweezers grip the head of the tick as close to your skin as possible.

- Pull steadily upwards, taking care not to crush the body of the tick.

- Do not be concerned if parts of the head of the tick remain in the skin but do apply a disinfectant and watch for other skin infections or irritation.

- Do not attempt to burn the tick off or use any substance to remove it.

References

www.hse.ie/eng/health/az/L/Lyme–disease/